|

|

|

|

Cave Formation and Preservation

|

Caves are more than geological marvels; they are time capsules that preserve a record of Earth's history towards an understanding of the origin of life on Earth. The outside environment has very limited influence on a cave's internals, being largely set apart from the effects of the fast evolving world above.

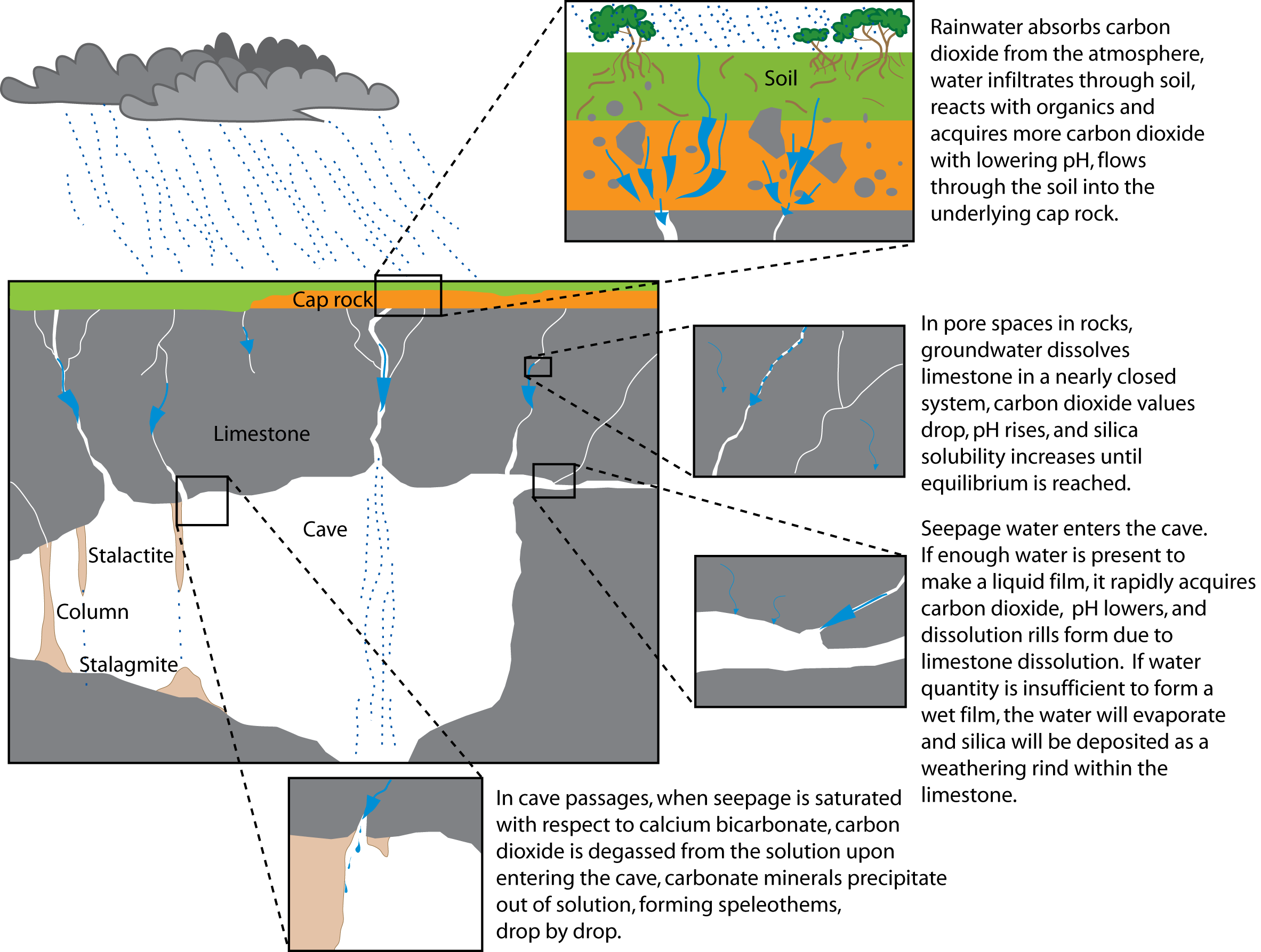

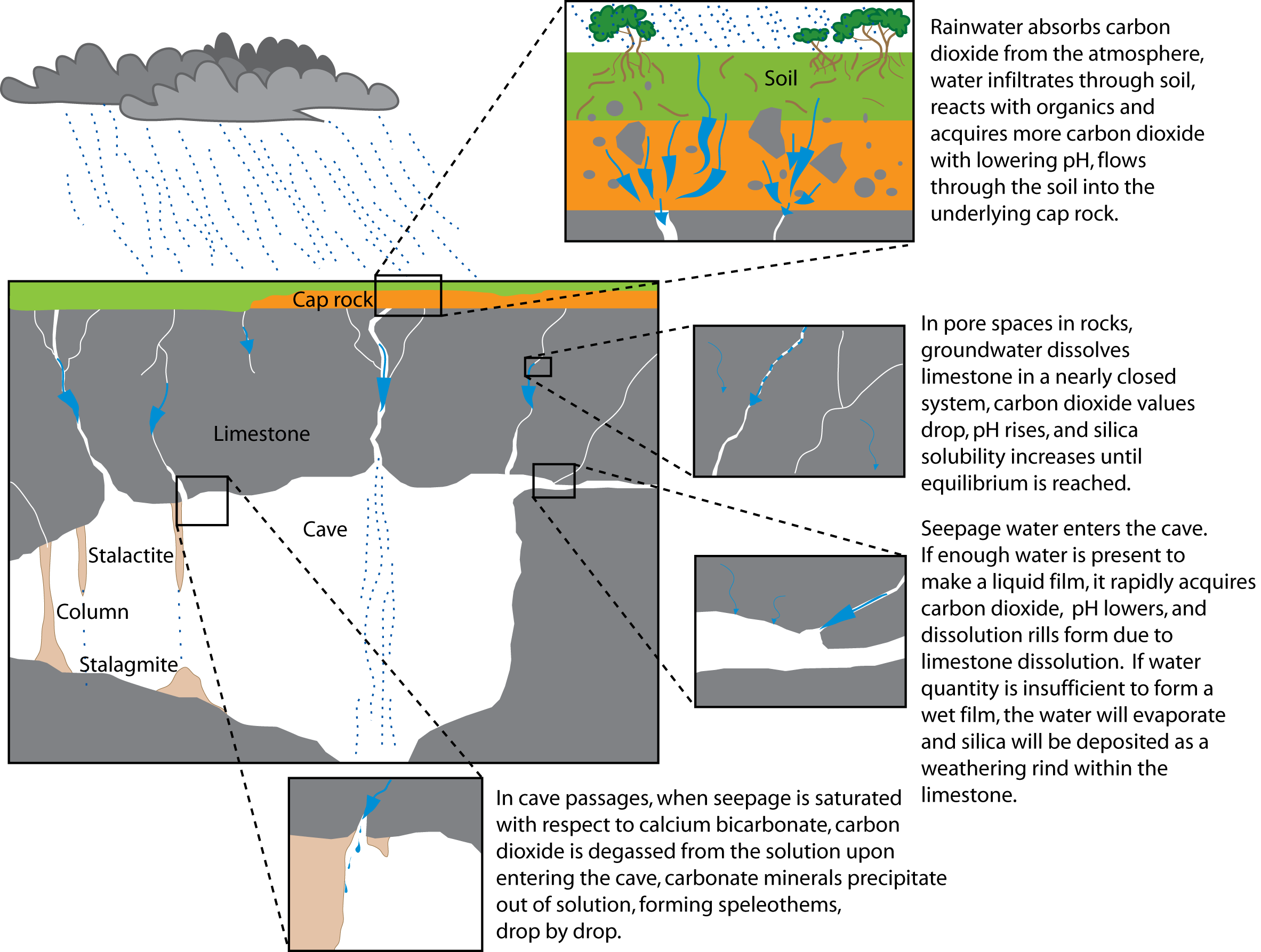

The formation of caves depends on several geological processes: wind, volcanism, tectonics, ice and dissolution in water. As a result, the majority of Earth’s cave systems are mainly represented by carbonate rocks, including when remarkable karst phenomena occur in gypsum, halite, and poorly soluble rocks such as quartzites.

The diagram to the right illustrates the formation of a karst cave system. The impact of climate, largely rainfall and carbon dioxide, are key to the formation process. Thus, demonstrating how a karst environment is extremely sensitive to changes in both climate and carbon dioxide.

Caves are unique geo-ecosystems as a result of their strong geodiversity, their relatively stable environmental conditions, the absence of strong seasonal modifications as well as permanent darkness. They can also be considered “conservative environments”, able to preserve information for a long period of time. As an example, information about past environmental and climate oscillations can be preserved in cave sediments (e.g. pollen content) and speleothems (e.g. calcite stable isotope composition, petrography, trace elements, etc.). Their specific environmental conditions can lead not only to the precipitation of rare speleothems and mineral phases, making these environments extremely interesting for earth science research. The creation of a specific habitat is extremely interesting for the study of ecological adaptation of both vertebrates, invertebrate species and bacterial colonies. The glowworm is one of many unique species which has evolved to survive in complete darkness.

The human population has expanded from 1 billion to 8 billion since 1800. This 700% increase has resulted in significantly growing demand to explore the underground world. Delicate cave environments, which have been preserved from the outside world for millions of years, are now facing significant anthropogenic threats. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Co2 Erosion |

Carbon dioxide is a key influence in karst cave formation. As a result, the internal environment is extremely susceptible to a change in CO2 levels; such as CO2 from human breath. If levels rise above 2400ppm, water within the cave becomes acidic and will corrode the cave formations. This can cause tens of thousands of years of damage. |

|

|

|

|

| Environmental Alteration |

To allow visitation within a cave, infrastructure is often installed to provide the necessary access to host high visitor numbers.

Man-made accessways and handrails are being built within caves, as recently as within 2023. These pathways have irreversible damage on caves and have triggered environmental concern. |

|

|

|

|

| Introduction of Light |

Show caves for tourism provide lighting throughout cave internals, including along internal pathways and to highlight certain natural cave formations. Artificial lighting has a significant effect on a caves ecosystem, particularly by allowing the growth of spores, which otherwise are unable to survive due to lack of light. |

|

|

|

|

| Temperature Changes |

With hundreds of visitors in a natural cave at any one time, heat from the human body can alter the temperature within a cave significantly in a very short timeframe. This temperature shift can have disastrous effects on troglobites and the carbonic reaction influencing the natural cave formations. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Clifden Cave, South Island |

|

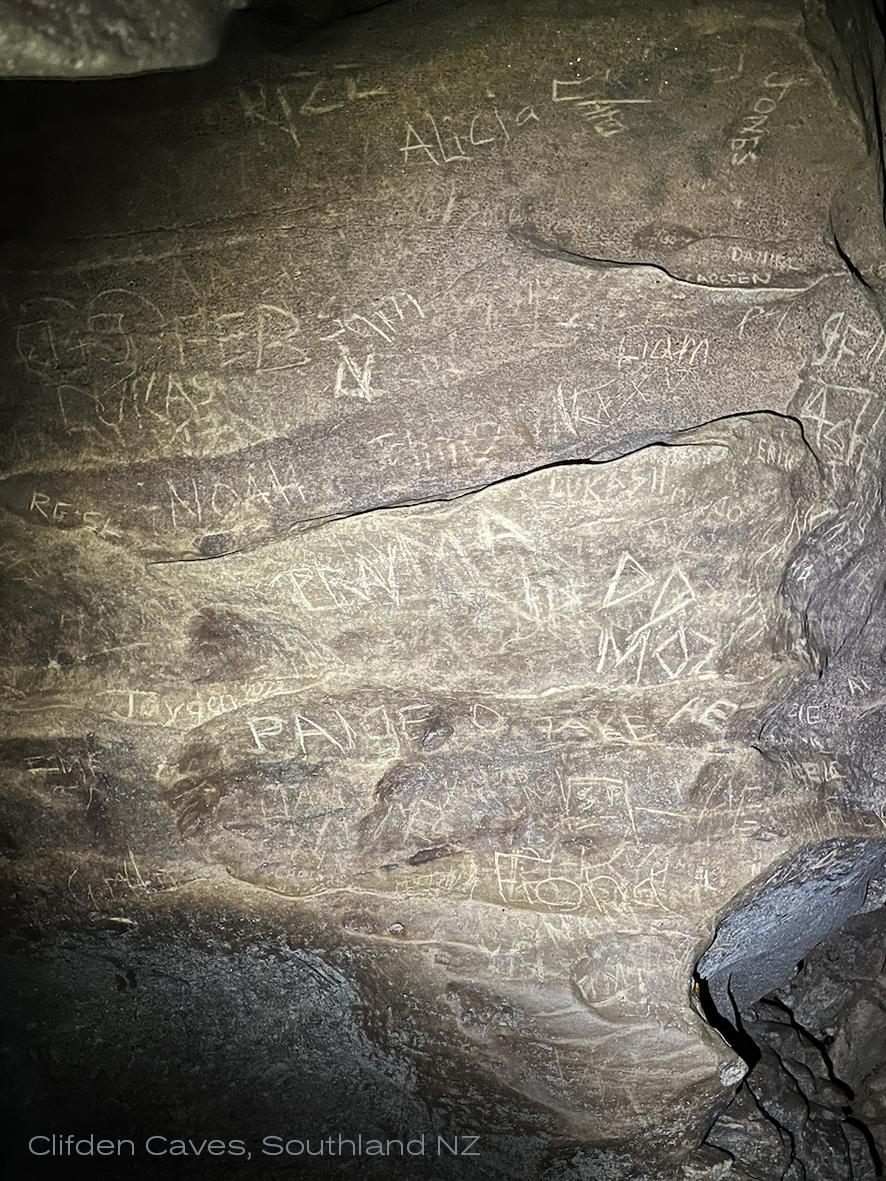

Southland's Clifden Cave is a 300m karst cave open for the public to enjoy. The cave is home to many natural delicate cave features and fauna, including glowworms.

Positioned in a remote location, the unregulated Clifden Cave has been susceptible to vandalism and graffiti.

Methods of graffiti in this cave include spray paint, engraving, pen and pencil.

Being an environment which has very little influence from the outside elements, such as erosion from rainfall, the majority of this graffiti will remain intact for thousands of years.

|

|

|

|

CO2 Management

|

Already in the 1970s, when visitor numbers were much lower than the current day, Waitomo Caves realised the impact visitor CO2 was having on the cave internals, and the glowworm population within.

This impact was first noticed when the glowworm population began to glow much less frequently. Through research, it has been understood that the species will stop glowing when in a stressed environment. It was discovered that visitor CO2 was reacting upon the cave surface to create carbonic acid, which was impacting the glowworm.

Initially, a solution undertaken was to vent the CO2 out through a new opening drilled into the cave wall. Although this 'blow out' effect was successful on a CO2 front, the change to the environment and impact this would have on the glowworm population was overlooked. As a result, the glowworm population decreased by 96% from its original population size.

Nowadays, Waitomo Cave is managed by an integrated monitoring system managed by NIWA. NIWA’s sensors communicate CO2 data in real-time from Aranui, Ruakuri and Waitomo Caves. They also measure air temperature, humidity, water level, water temperature and cave door status. |

|

|

|

| Waitomo Caves Discovery Centre educator writes about the science education that takes place within these unique natural formations.

|

"Human intervention during 1975-1979 to control the ‘blow out’ of excess carbon dioxide gas, which caused the limestone decorations to corrode, was almost a disaster for the glowworm population.

Removing the top cave door to allow air to flow through the cave and flush out CO2 also caused glowworm desiccation and stress, resulting in a mass die-off.

|

|

Now, an environmental officer employed by the cave operator monitors the glowworm population and manages the corresponding data.

This data is recorded as a photograph every 30 minutes, where glowworm number and light intensity is captured.

The glowworm is an important environmental bio- indicator, which in 1979 had reduced to only 4 per cent of its normal population size, causing the cave to close for several months. It also resulted in the formation of a scientific advisory group to protect the cave’s ecology." |

|

|

|

|

|

|

NIWA writes about their subterranean sensing

|

"We’ve known for decades that high CO2 levels are bad for the caves. Things start going downhill at 2400 parts per million. That threshold was determined by the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research in the 1970s.

Environmental monitoring technician Carl Fischer says there’s a fine balance between letting people in to enjoy the caves and protecting the caves from damage. “On the one hand, the cave operator has visitors who are a source of CO2. On the other hand, they have a consent requirement that CO2 doesn’t exceed the threshold. Monitoring is needed to demonstrate compliance with the threshold and manage visitor numbers.”

It took a collapse of the Waitomo Glowworm Cave glowworm population in the 1970s to realise just how finely tuned things need to be.

CO2 has a big effect on precipitation processes that create speleothem cave formations. The most well-known types of speleothem are stalagmites (which grow from the ground up) and stalactites (from the roof down)."

|

|

| Tourism Holdings CEO, Grant Webster, discusses the challenges of managing Waitomo Caves CO2 levels |

"One of New Zealand's most popular tourist attractions, the Waitomo Glowworm Caves, had to shut up shop a number of times over summer because of excessive carbon dioxide levels, driven partly by visitor numbers.

The chair of the cave's environmental advisory group is worried what burgeoning tourist numbers could mean for the cave, and said the potential to damage it was very high.

About half a million people visit the Waitomo Caves every year, making them the most-visited caves in the Southern Hemisphere.

|

|

Tourism Holdings is the leaseholder and operates the Discover Waitomo Group, which includes the Waitomo Glowworm Caves, Ruakuri Cave and Aranui Cave

The chief executive of Tourism Holdings, Grant Webster, said the glowworm caves have been shut down about five times over summer because the level of carbon dioxide in the caves has gotten too high.

He said this was not isolated, and had happened over the last few years.

The glowworm caves could be closed anywhere from half an hour to a few hours and visitors were usually very understanding when it happened." |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The walls of the Lascaux cave are decorated with 17,000-year-old paintings, some 600 painted animals and symbols, as well as nearly 1,500 engravings.

||

The Lascaux grotto was opened to the public in 1948 but was closed in 1963 due to anthropogenic damage. The breath of visitors created carbon dioxide and humidity, which was causing irreversible damage to the paintings, and the introduction of artificial lights had encouraged algae to grow upon the cave walls.

To preserve the Lascaux cave, the government initiated that in 1983 a replica was opened instead. The sole aim was to allow the public to enjoy the cave drawings without causing damage to the natural cave itself.

In December 2016, a new and near perfect replica to the original cave was opened. The French government had spent $64 million on this state of the art preservation project. The initiation of the replica Lascaux cave has placed France as no1 in the 2017 Economist Sustainable Tourism Index. The Lascaux cave replica received special recognition in the report.

|

|

The Chauvet Cave in southeastern France is a cave that contains some of the best preserved figurative cave paintings in the world. Discovered in 1994, it is considered one of the most significant prehistoric art sites and the UN’s cultural agency UNESCO granted it World Heritage status in 2014.

The cave has been sealed off to the public since 1994. Access is severely restricted owing to the experience with decorated caves such as Altamira Cave and Lascaux Cave, where the admission of visitors on a large scale led to carbonic acid erosion and the growth of mold on the walls that damaged the art in places.

Caverne du Pont-d'Arc, a facsimile of Chauvet Cave on the model of the so-called "Faux Lascaux", was opened to the general public in April 2015. It is the largest cave replica ever built worldwide, ten times bigger than the Lascaux facsimile. The art is reproduced full-size in a condensed replica of the underground environment, in a circular building above ground, a few kilometres from the actual cave. Visitors’ senses are stimulated by the same sensations of silence, darkness, temperature, humidity and acoustics, carefully reproduced.

|

|

|

Professor Chris De Freitas

University of Auckland

|

Waitomo Cave external environmental advisory group Chair

University of Auckland Deputy Dean of Science and Pro Vice-Chancellor

Vice-president of the Meteorological Society of New Zealand

Vice-president of the International Society of Biometeorology

Co-founder of the Australia New Zealand Climate Forum

Editor of the international journal Climate Research

Credited with more than 200 publications, including two recent books, New Environmentalism: Managing New Zealand's Environmental Diversity, and Natural Hazards in Australasia.

De Freitas was three times the recipient of the New Zealand Association of Scientists' Science Communicator Award. |

|

"Despite the importance of caves as natural resources and their great sensitivity to damage, little or no legislation is in place to protect them. It highlights a serious blind spot in environmental management.

Unlike other environmental assets, such as native forests that are resilient and can grow back from total destruction, most damage to caves and surrounding limestone landscape is irreversible.

There are direct and indirect impacts to consider.

Direct impacts include breakage of delicate stalactites and stalagmites, construction of access routes through caves, alteration of the cave microclimate from entrance modifications and visitor numbers, the build-up of carbon dioxide in the cave from human breath that combines with moisture to corrode limestone features, accumulated lint from clothing (on which bacteria feed), and heat from people and lights.

Many of these impacts are cumulative and often lead to irreversible degradation to the cave ecosystem."

|

|

|

Articles by Professor Chris De Freitas

|

|

| Precious caves at risk in legislative vacuum |

"Despite the importance of caves as natural resources and their great sensitivity to damage, little or no legislation is in place to protect them" |

|

|

|

|

|

| Waitomo Caves shut 'five times' due to high CO2 |

"He said this was not isolated, and had happened over the last few years" |

|

|

|

|

|

| Threat to Waitomo Caves a threat to the nation |

"Small caves and those hosting cave fauna, such as glowworms, are particularly vulnerable" |

|

|

|

|

|

| Trouble in the air at Waitomo Caves |

"This stresses the glow-worms and, over time, corrodes the limestone features which take hundreds of thousands of years to develop" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|